April, 1999

Government Bargaining With Non-Unitary-Actor Parties And

The Case of Italian Government Breakdowns

Ram Mudambi

Case Western Reserve University and University of Reading

Pietro Navarra

Università degli Studi di Messina

Abstract

We use the game-theoretic bargaining model between heterogeneous organisations to analyse coalition bargaining for government formation. The game is characterised by the presence of n-person political parties which are assumed to behave as non-unitary-actors. Party members therefore attach different levels of utility to the two possible outcomes of the game: government continuing support or a Parliamentary vote of no-confidence. Our theoretical model is then applied to the Italian political environment in order to explain the rise and fall of coalition governments in a time span embracing the years 1994-1999. The paper thus attempts to reach two objectives. First, to design a theory about the dynamic process of government formation through the theoretical definition of the core of the bargaining game. Second, to offer a consistent game-theoretic explanation of the ups and downs of Italian governments in the years following the implementation of the Italian electoral reform.

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Peter Bernholz and participants at the European Public Choice Society Meeting in Lisbon for helpful suggestions. We acknowledge also Bernard Grofman, Guillermo Owen and Giuseppe Sobbrio for stimulating discussions. The usual disclaimer applies

Address for Correspondence:

Pietro Navarra

Istituto di Economia e Finanza Email: navarrap@www.unime.it

Università degli Studi di Messina Phone: +39 090 6764446

Piazza Pugliatti 1, 98100 Messina FAX: +39 090 719202

Italy

FOREWORD

It can certainly be said that, in one way or another, all aspects of an economist’s understanding of political phenomena have been influenced by the ideas and insights of James M. Buchanan. His research has profoundly influenced the research of others in all of the social sciences. Hence, it is not surprising to that our work has been deeply affected by his writings.

In putting together this special tribute to Jim Buchanan on the occasion of his 80th birthday, we would like to give an example of how Buchanan’s teachings have affected the way we look at Italian politics. In several of his writings he taught us that rules matter. He also suggested that in the case of constitutional evolution and change the power of the new rules is modulated by embedded institutions. In our recent research we studied the effects of the new system of representation in Italy on a party system that did not want that change and resisted it both fiercely and subtly.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the debate over the competing merits of alternative systems of representation one of the most interesting aspects that attracted the attention of public choice economists, political scientists and technical observers has been the role provided by different electoral rules to the electoral body. In this respect the classical distinction between the system of proportional representation (PR) and the plurality electoral rule (PL) is based on the fact that the former is designed to ensure representation in the elected assemblies, while the latter to guarantee effective government.

In the beginning of this decade Italy has experienced the change of its electoral rules from a system of PR to a PL system. As expected, the electoral reform brought about important consequences for both the process of government formation and the achievement of government stability over the electoral mandate. As just pointed out, with the new PL system of representation voters directly choose their government, while under the old PR governments were formed in the Parliament after the election. This change can have different implications according to the party system in place in a given country.

In a country characterised by two-party politics, the voters’ mandate for government formation is addressed either to one party or to the other. The victorious party (i.e. the one obtaining the majority of the seats in the Parliament) is the party backing the new government and its leader is often the head of the executive. In these cases, the system of representative democracy is given only two possible options: either the government lasts the entire time of the legislature or there is a call for fresh elections. No other government can be formed (i.e. voters choose their government) is safe.

Things become more cumbersome when we apply the PL principle for government formation in multi-party system. In the simplest case, in multy-party electoral competition political parties alternatively join two opposing coalitions. The political parties forming the victorious coalition (i.e. those obtaining the majority of seats in the Parliament) are expected to support the new government and the coalition leader is expected to be at the head of the executive. In multy-party electoral competition with coalition governments, the system of representative democracy is given more than just two options: the government can last the entire time of the legislature, the government can collapse and fresh elections follow and, finally, the government can collapse and a new government get formed. As in the case of two-party politics, the first two options preserve the principle governing PL electoral rule (i.e. voters choose their government). In the third case, however, the power of choosing the government is taken away from voters and it is transferred to the elected representatives in the Parliament. The PL principle is betrayed and some re-borne PR elements determine the composition of the new government.

In this paper we construct a game-theoretic bargaining model between heterogeneous political parties. Our model describes the dynamic process of government formation and continuation in office in multi-party context. The model is designed in such a way to explain the rises and the falls of the Italian coalition governments that followed the implementation of the electoral reform. In other words, our objective in this paper is twofold. First, we build a theoretical model in the attempt to describe the working of the PL underlying principle for government formation and continuation in office. Second, we apply this model to shed some light on the nature of the Italian multi-party coalition government that were formed after the implementation of the electoral reform.

This study is structured as follows. In Section 2 we construct the game-theoretic model of government bargaining with parties acting as non-unitary actors. In Section 3 we open a discussion over some implication of our theory for the working of the new Italian system of representation. In Section 4 we draw some concluding remarks.

2. THE MODEL

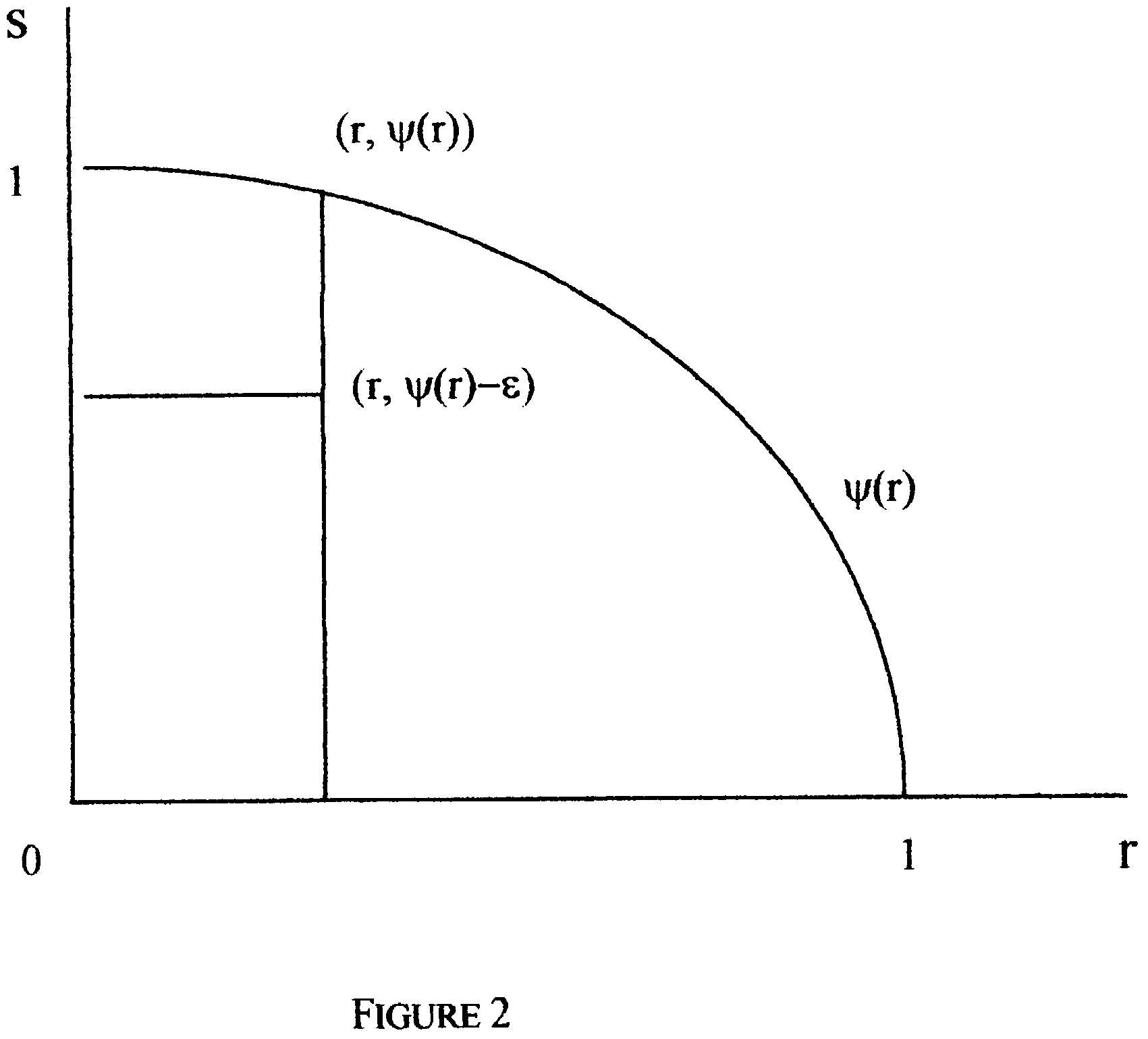

We model the formation of a government made up of more than one political party in a two-stage game. In the first stage electoral alliances are formed. These alliances fight the election. In the second stage the parties in the winning alliance bargain over the division of net benefits from office. This game may be described in Figure 1.

If the electoral alliance is defeated, we assume that there is not strategic decision making in Stage 2. If the electoral alliance is victorious, it forms a government. We model Stage 2 as a bargaining situation in which the alliance partners negotiate over the division of the benefits that flow from office. These negotiations continue during the life of the government and the outcome determines whether the government survives. For simplicity, we assume that the victorious alliance consists of two parties X and Y. Only two outcomes are possible - either the two parties agree on the division of benefits and continue support the government or they do not. If they do not agree, they are forced to fight a new election. Neither X nor Y is homogeneous - they are both heterogeneous groups in which there is division of opinion over the benefits of government continuation. Government continuation requires that the parties in the alliance jointly endorse a policy platform. The policy platform implies the division of the benefits of office amongst the elected representatives of X and Y.

The game in Figure 1 is solved by backward induction. Therefore, the bargaining for government continuation in office must be approached first.

Setting up the Stage 2 Game

The benefits that representatives enjoy from government continuation in office may be direct, in the sense that they receive pecuniary or other rewards for being in government. They may also be indirect, in the sense that the benefits may flow to the representatives’ constituents. The actual perceived benefits of the representatives may be viewed as a combination of these direct and indirect benefits. There are also indirect costs from being in government. Being a member of a government whose policies are considered to be inimical to the interests of a representative’s constituents can lower his or her re-election chances. In deciding whether or not to support the continuation of a particular alliance government, each representative compute his or her benefits from being in such a government.

We assume that the representatives of X and Y can be ordered along a single dimension in terms of their net benefits from agreement (and consequent government continuation). We also assume that a greater share of the total benefits accruing to a party implies a higher level of net benefits for all its representatives. The greater the share of the total benefits from the continuation of government that flow to one party, the greater the proportion of its representatives that will support agreement, Thus defining ‘mX’ to be the share of the total benefits from agreement flowing to party X and ‘r’ to be the proportion of party X representatives supporting agreement, we can write

r = r(mX), 0 £ r £ 1, r¢ > 0 (1a)

Similarly, defining ‘s’ to be the proportion of party Y representatives supporting agreement:

s = s(mY), 0 £ s £ 1, s¢ > 0 (1b)

Representatives of both parties located close to 0 are those with high net benefits (and low costs) from government continuation, while those located close to 1 are those whose net benefits may even be negative, since they have very high costs. Given that the representatives from X and Y are distributed along a single dimension in terms of their net benefits from agreement, both r(.) and s(.) can be viewed as distribution functions defined over the [0,1] interval.

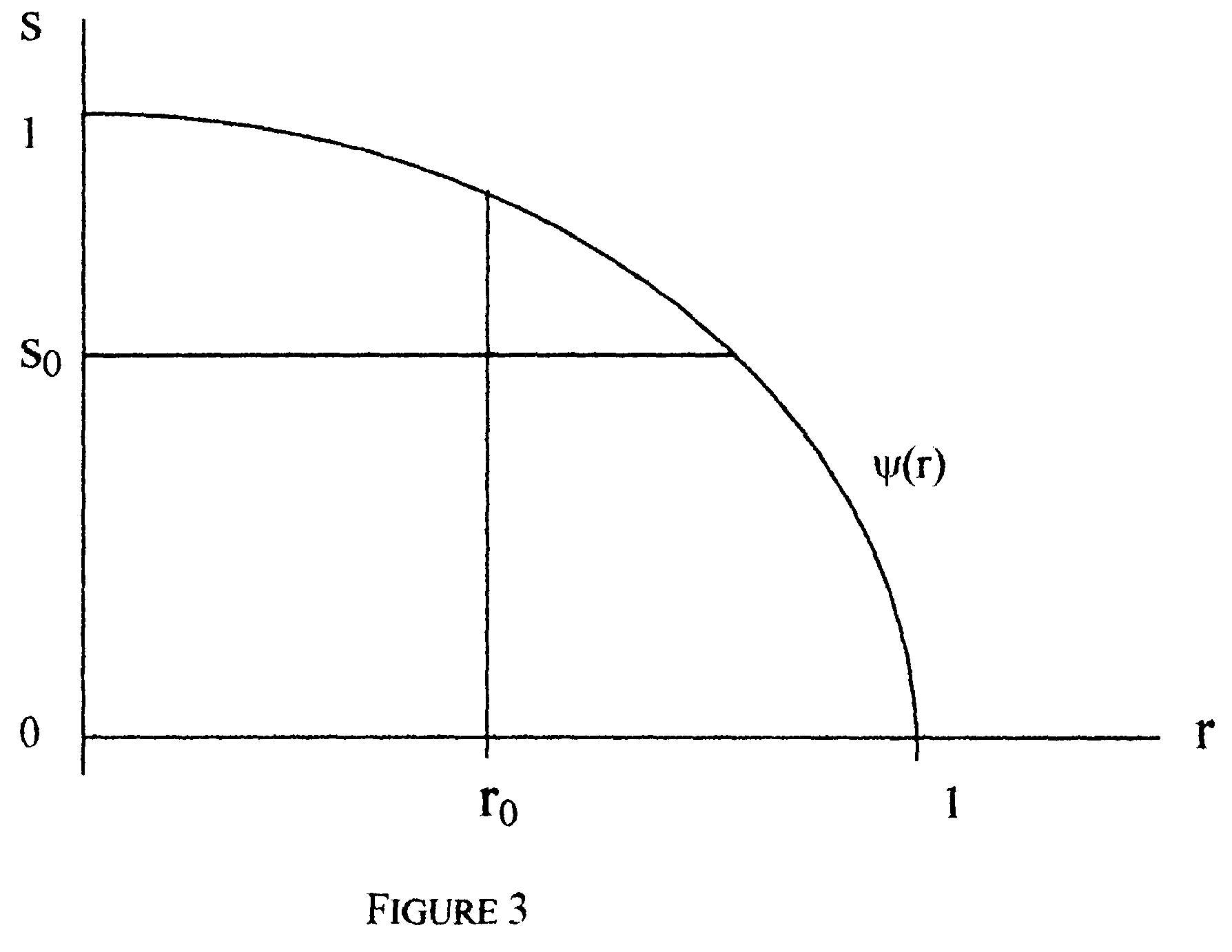

The division of the total benefits from government policy implementation between the two parties may be represented on a two dimensional plane (see Figure 2). Feasible agreements are those points of the plane where the shares of net benefits of the two parties sum to less than or equal to unity. Infeasible agreements are those points where the shares sum to more than one. If party X enjoys all the net benefits, then all representatives of party X support government continuation. However, no representatives of party Y can support continuation of the government, since they have nothing to lose from fresh elections. If a small portion of the net benefits are transferred to party Y, these (by definition) go to those representatives with the most to gain from government continuation. As a greater portion of the net benefits are transferred to party Y, a greater percentage of party Y representatives (and a smaller percentage of party X representatives) favour government continuation. At the other extreme, when all the net benefits of government continuation are enjoyed by party Y, all Y representatives (and no X representatives) favour government continuation.

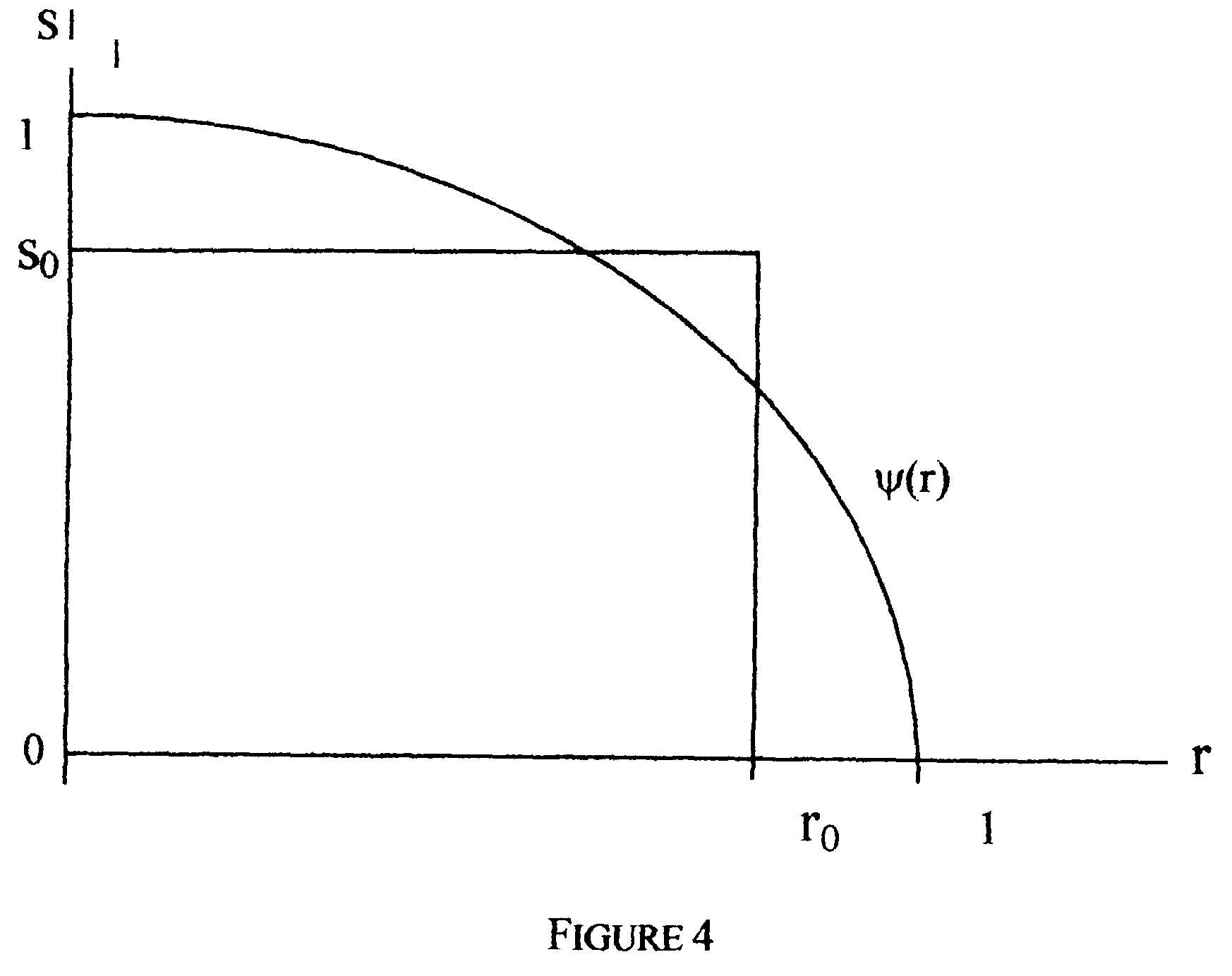

For a given share of net benefits, ‘m’, given to party X, the maximum available net benefits for party Y may be defined as y (r). As defined above, r is the proportion of party X representatives who prefer the level of net benefits implied by the share ‘m’ to fighting fresh elections. As shown in Figure 2, the function y (r) may be assumed to be monotonically decreasing concave function (party X and part Y are heterogeneous groups and have different valuations of the combination of benefits along y (r)). Any point in this space represents a division of benefits between the two parties and may be defined to be an agreement. In other words, at the point [r, y (r)], party X receives m% of the benefits and party Y receives (1-m%). At a point like [r, y (r)-e ], which is inside the function y (r), party X continues to receive m% of the benefits, but now party Y receives less that (1-m%). Therefore, the function y (r) may be defined to be the set of Pareto-efficient agreements. Such Pareto-efficient agreements have the property that mX + mY = 1.

Government Survival

The government can only remain in office if a sufficiently set of representatives agrees to continue to support it. We define such a set of representatives to be a pragmatic government coalition, to be distinguished from the electoral alliance, consisting of the entirety of the two parties. In the case of two parties, a pragmatic coalition consists of a set of representatives containing at least a fraction r0 of party X and at least a fraction s0 of party Y, where both r0 and s0 lie between zero and unity. The existence of a pragmatic coalition guarantees the survival of the government in office, while the existence of a blocking coalition ensures fresh elections.

The utility of individual representatives is determined by their net benefits in the case of government continuation. In the case of fresh elections, all representatives incur campaign costs ‘C’. We can write the utility of the ith representative of party X as:

ux = ux(mx - ci) if government survives

= -C if there are fresh elections (2a)

A representative of party X support agreement if ux(mx - ci) > -C. If ci is very small, the representative will almost always find it in his or her interests to support agreement. Thus such a representative occupies a position very close to 0 in the distribution function r(m). On the other hand, if ci is very large, the representative will almost never find it in his or her interests to support agreement. Such a representative occupies a position very close to 1 in the distribution function r(m).

We can write the utility function for the jth representative of party Y as:

uY = uY(mY - cj) if government survives

= -C if there are fresh elections (2b)

Again, a representative of party Y supports agreement if uY(mY - cj) > -C. Following a similar analysis to that presented in the case of party X, low cj representatives are located close to 0 and high cj representatives are located close to 1.

We will analyse the bargaining situation between party X and Y by looking for the game-theoretic core. We may define

mX0 = r-1(r0) (3)

Similarly, we may define mY0 = s-1(s0).

A pragmatic coalition may be constructed in the following way: (1) identify the marginal representative in both parties who is just indifferent between agreement and fresh elections; (2) agglomerate the infra-marginal representatives in both parties. It may be seen that this is the easiest pragmatic coalition to construct. The marginal representatives in party X and party Y are, respectively, identified by

ux(mx - ci) = -C

uY(mY - cj) = -C (4)

By construction, such a coalition includes a proportion r0 of party X representatives and a proportion s0 of party Y representatives and is therefore a pragmatic coalition.

Equilibrium in Stage 2 Game

There are two possible equilibrium outcomes to stage 2 game. One involves agreement and government continuation and the other involves disagreement, government collapse and fresh elections. It may be shown that if

s0 £ y (s0) (5)

then there exist an agreement in the core of the game. If this is true, so that the core is non-empty, then a division of total benefits (r,s) as shown in Figure 3 is in the core (which implies that it is also Pareto-efficient) if:

r ³ r0; s ³ s0; and s = y (s0) (6)

An agreement (r,s) is not in the core (see Figure 4) if either

r < r0; s < s0

If the first inequality holds, the proportion of representatives from party X for whom ux(mx - ci) > -C is larger than (1- r0) and they form a blocking coalition since they are better off with fresh elections than with government continuation. Similarly, if the second inequality holds, there is a large enough proportion of representatives from party Y who are better off with fresh elections than with government continuation, and they form a blocking coalition.

The second equilibrium outcome involves disagreement. It may be shown that this equilibrium obtains if

s0 > y (s0) (7)

If this is true, then it is clear that it is impossible to form a pragmatic coalition. This is because the condition implies that mX 0+ mY0 > 1. Any division of benefits supported by the minimum proportion of party X representatives (r0) implies a share for party Y that is too small to achieve minimum support, i.e., 1 - mX 0< mY0. Hence, any agreement will face a blocking coalition from within at least one of the two parties. The only possible equilibrium is disagreement and a return to the electorate for a fresh mandate.

Extending the Stage 2 Game

What happens if we drop the assumption that the representatives’ preferences are ordered over a single dimension? This assumption allows us to write their utility functions as in (2). Thus, even though the parties may consist of may internal factions, one faction must necessarily have the highest cost to remaining in government. In each party, these factions can affect the minimum sizes of the pragmatic coalitions (r0 and s0), and hence the equilibrium outcome of the game. This will be particularly important if a pragmatic coalition cannot be formed without minimum participation from particular factions.

If representatives’ preferences are ordered over (for example) two dimensions, the benefits and costs (and hence net benefits) to remaining in government must be evaluated along both these dimensions. The share of overall benefits enjoyed by party X can be written as

MX = [d1, d2], 0 £ d1 £ 1, 0 £ d2 £ 1

where the elements are measures of the shares of the two distinct benefits. In examining the make-up of a pragmatic coalition with internal factions within parties, two cases are possible.

In the first case, focusing on party X, one faction has the highest cost to remaining in government along both dimensions. In this case, ensuring the support of this faction for an agreement will automatically ensure the support of all others. Therefore, this faction enjoys a control position in the party and its preferences determine the critical values of MX0 (which corresponds to (3) above). A similar analysis can be applied to party Y to determine MX0.

In the second case, again focusing on party X, one faction has the highest cost to remaining in government along one dimension, but some other faction has the highest cost along the other dimension. In this case the support of any one faction for an agreement will not automatically guarantee the support of all the others. However, it must be true that one faction has the highest cost along each dimension. Hence, one faction will determine the critical value of one element of MX0 and another faction will determine the critical value of the other element. Now, these two factions enjoy controlling position in party X. Obviously a similar analysis applies to party Y.

It may be seen that the maximum number of factions in controlling positions is at most equal to the number of dimensions over which the representatives’ preferences are defined. Finally, these preferences of the party X and party Y representatives determine an ordering over agreements regarding government continuation in office.

3. DISCUSSION

The electoral system for the election of the Italian National Parliament was reformed in 1994. The electoral rules were altered from a pure system of proportional representation towards a plurality first-pass-the post system with single-member colleges. The new system of representation was designed to allow voters to choose the government, as opposed to representing all different opinions in the legislative assembly. These electoral rules allow voters to directly choose future governments, rather than allowing the elected representatives decide in their behalf. In multi-party electoral contests where no single party is likely to achieve the majority in the legislature, coalition government are most likely to occur. In such cases, the PL rationale applies to opposing political coalitions rather than opposing political parties. In this framework, in PL elections, voters choose the coalition they prefer to form the government.

In this paper we deal with coalition bargaining for both government formation and its continuation in office. It is well known that a change in the electoral system has some implications for government formation and stability. For the purpose of this study, the important point to be noted is that in Italy, PL electoral rules lead to coalitions being formed for the purpose of fighting elections. Therefore, coalition bargaining for government formation takes place at district level. Thus, voters are able to express their preferences over these coalitions. However, under PR electoral rules, individual parties fought elections and coalition government were formed in the parliament, after the election.

In our earlier papers commenting on the effects generated by the electoral reform on the Italian political system, we stressed a possible trade-off between what we defined as electoral coalitions and political coalitions. The former are coalitions designed with the aim of winning seats in single-member colleges, while the latter are coalitions engineered to form stable and long-lasting government. If the two coalitions are the same, i.e., the same parties join together to both win the election and govern the country, the principle of PL electoral rule (voters choose their own government) is fully operational. On the other hand, if the coalition of parties that won the election is different from the one governing the country, the political establishment betrays the principle behind the PL system of representation, since voters do not choose the government. This transfer of mandate for government formation from the electorate to the elected representatives could be viewed as a subversion of the objectives of the PL electoral rules in multi-party electoral competition. The possibility of such subversion nullifies one of the most important elements distinguishing the role of voters in the two conflicting systems of PR and PL.

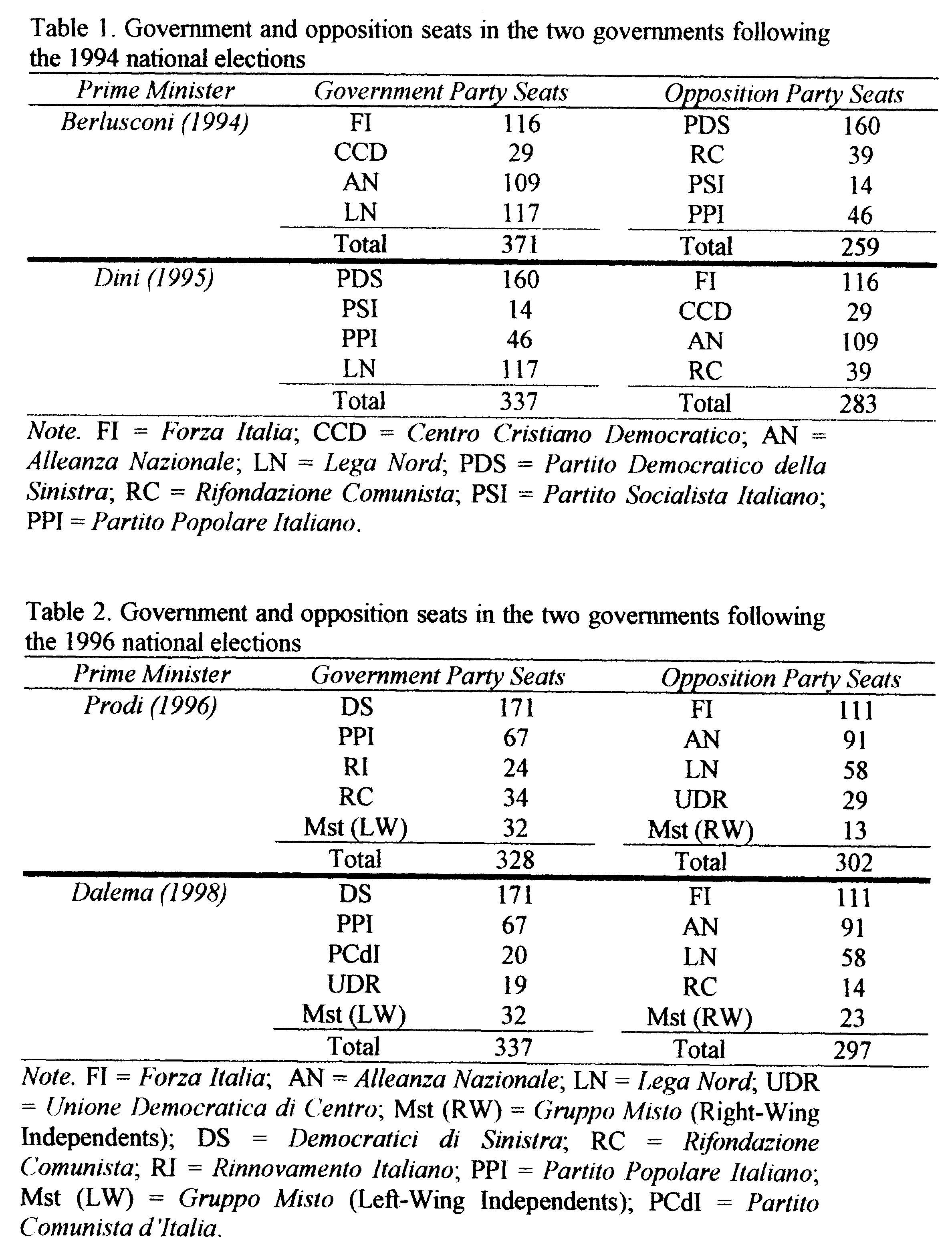

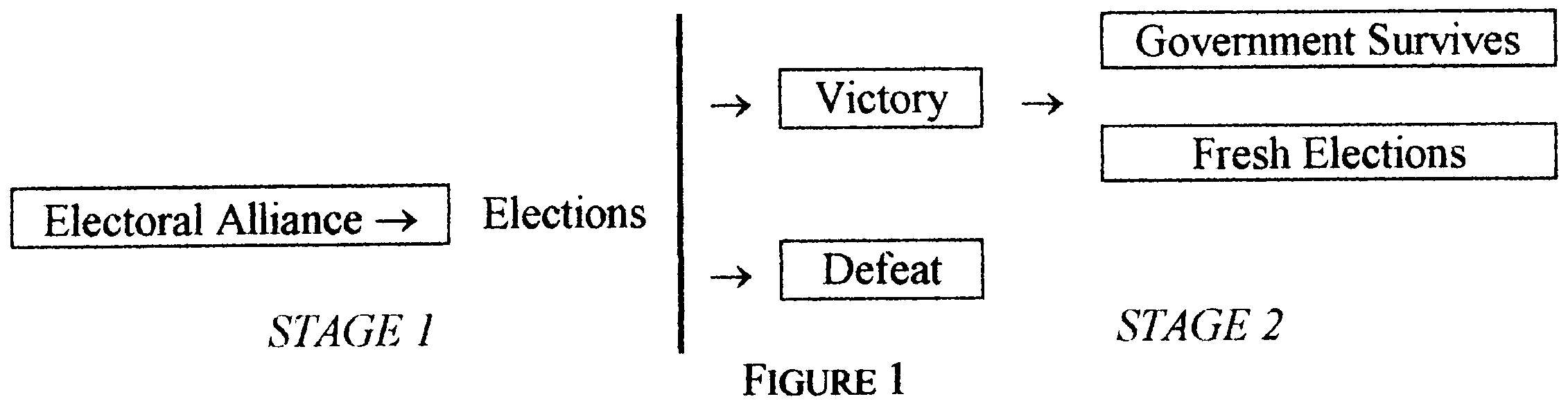

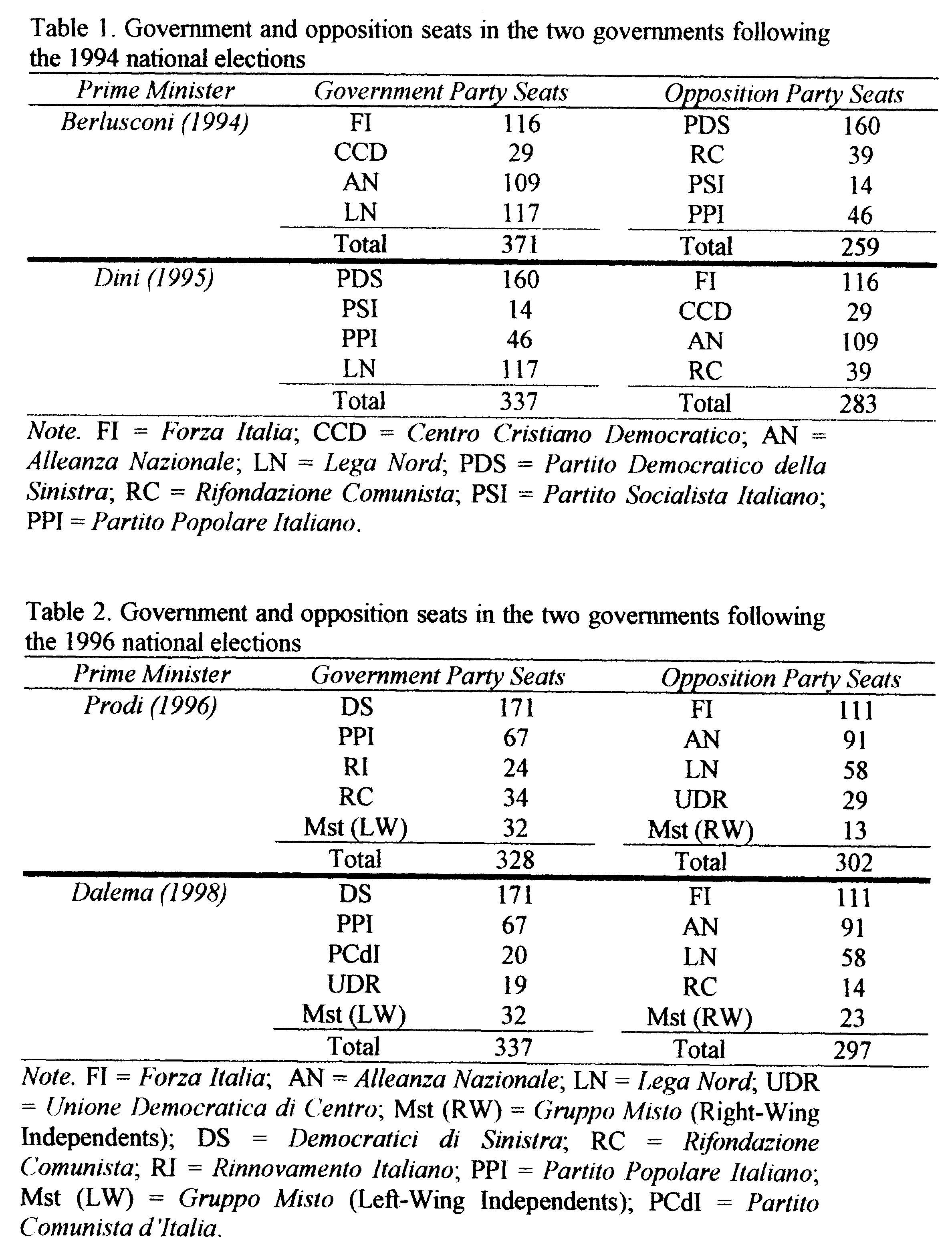

In the six years following the electoral reform (1994-1999) two national elections took place. During this period four different governments were formed, each supported by different parliamentary majorities (see Table 1 and 2). This indicates that the subversion of the PL rules in the multy-party system is a consistent feature of current Italian politics at national level. Examining Tables 1 and 2, we note that the formation of the Dini (1995) and Dalema (1998) governments are in stark contrast to the will of the Italian voters for two main reasons. First, voters chose a coalition of parties with the expectation that the office of Prime Minister would be filled by Mr. Berlusconi and Mr Prodi respectively in 1994 and 1996 national elections. Second, the coalition that obtained the majority of the Italian vote in 1994 and 1996 are different from those backing the two governments respectively of Mr. Dini and Mr. Dalema, i.e., coalitions were formed in the legislature without the sanction of the voters. This represents a reversion to the PR system of government formation that the changed electoral rules were designed to prevent.

The performances of the Italian governments coupled with the subversion of the objectives of the PL electoral rules in multi-party electoral competition can be viewed as an example of the resistance of the party system to the effects generated by the new system of representation. One would have expected that the implementation of the PL electoral rules would have implied the correspondence between the number of elections and the number of governments. However, in Italy the party system prevented this phenomenon to occur, distorted the underlying principle of the electoral system currently in place and diminished the role of voters in the selection of the government.

What has happened can be understood as an indirect attempt of the party system to restore the dynamics of government formation and continuation in office as they were under the old PR electoral rules. This misuse of the PL rules governing the system of representation caused two important political consequences for government formation and its continuation in office: it ensured a more active role for elected politicians in the Parliament and humiliated the expression of the electoral choice by voters.

4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this paper we have used a game-theoretic framework to describe the electoral properties of the Italian system of representation after the reform. In particular we focused our interest in modelling the effects the new electoral rules (PL system) concerning the Italian government formation and its continuation in office. Specifically, we modelled the formation of a government made up of more than one political party in a two-stage game. In the first stage electoral alliances are formed. These alliances fight the election. In the second stage the parties in the winning alliance bargain over the division of net benefits from office. In line with the principles supporting PL election rules, two are the possible outcome of our game: either the parties agree on the division of benefits and continue support the government or they do not. If they do not agree, they are forced to fight a new election.

The theoretical model is then applied to explain the Italian government turnovers after the implementation of the electoral reform. We noted that the Italian politics experienced a transfer of mandate for government formation from voters to the elected representatives. This phenomenon has been interpreted as a subversion of the objectives of the PL electoral rules in multi-party electoral competition. The possibility of such subversion to occur represents a reversion to the PR system for government formation that the changed electoral rules were designed to prevent.

REFERENCES

McCornick, G. H. and G. Owen (1998). Bargaining Between Heterogeneous Organisations. Unpublished Manuscript, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California.

Mudambi, R., P. Navarra and G. Sobbrio (1999). The Electoral Cost imposed on Political Coalitions by Constituent Parties: The Case of Italian National Elections, in R. Mudambi, P. Navarra e G. Sobbrio (eds.), Rules and Reason: Perspectives on Constitutional Political Economy, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mudambi, R., P. Navarra and G. Sobbrio (1999). Party Strategies and Voting Behaviour: The Political Economy of Italian Electoral Reform, Aldershot: Edward Elgar.